The Siskiyou Nature Man

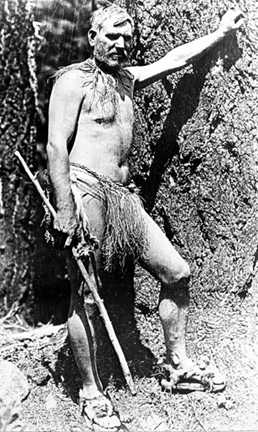

Joe Knowles in clothing he made from the Oregon forest. Photographed during a visit to his wilderness camp in the Siskiyou Mountains on August 8, 1914 and described in an Oregonian article on August 9, 1914 (20). Photo from Josephine County Historical Society.

You can only imagine how people reacted when, in the summer of 1914, a man arrived in Grants Pass, Oregon and announced he was going to strip off all his clothes and go naked into Siskiyou Mountains for two months and survive using his bare hands and instincts. He called it his “man against nature” experiment and proposed to make his own clothes and shelter from what he found in the forest and eat only what animals he could catch or berries he could find, all of which would be done in complete isolation from human interaction.

The stunt may have seemed strange but people where probably not that surprised with his proposal because in the previous year he was involved in a widely publicized, naked-in-the-woods experiment in Maine where hundreds of thousands of people came out to greet him when he returned. It was this widely publicized demonstration of man against nature that he was hoping to duplicate in Josephine County.

1913 – Maine

His name was Joseph Knowles, a self educated artist who participated in a “man against nature” publicity stunt for the Boston Post. Widely touted as the “Yankee Tarzan”, he began the stunt by stripping down to complete nudity and entered the wilderness of Maine in August of 1913 without firearms, matches, or even a knife. Under these conditions, he lived for two months as a primitive man, relying on his own resources to survive.

Knowles had suggested this venture to the Boston Post earlier that same year and the newspaper quickly snatched up the idea as a possible way to hoist slumping circulation. The setup was simple. Knowles would live for two months in isolation, and would record his adventures on birch bark with the charcoal of burned sticks. Each week he would leave one of these reports in a predesignated cache where a reporter would retrieve it and expand Joe’s message into a feature-length article.

During the 61 days he was in the woods, most of New England, New York, and every other area served by the Post’s special syndication followed his adventures. The reports he wrote were often highly dramatic including tales about wrestling a deer to the ground with his bare hands and killing a bear with a club. The Post’s circulation more than doubled as Knowles reports revealed that he lived on roots and berries and made sandals out of bark, and later, made clothes and moccasins out of the skins of the deer he had killed. City dwellers could barely wait for the next installment to read of Knowles’ exploits thereby creating a front-page story that held the nation spellbound for more than two months.

After two months, he emerged from the wilderness in Canada and was brought home by train. At each stop made by the train, he would put on the bear skin robe and moccasins and greet the crowds who gathered to see him. It was reported that eight to ten thousand people gathered at railroad stations along the route and schools had been dismissed so that the children might have a unique educational experience of seeing the “modern primitive man”, a sight they would likely never see again.

When the train arrived in Boston, a crowd of well-wishers filled the station and spilled out into the surrounding streets. Standing up in the car that took him on an “auto parade” through the streets of Boston, Knowles waved as they moved slowly through dense throngs that wanted to shake hands or touch the wild skins of the “hero of the twentieth century”. Two or three women tried to climb into the car with the “caveman”. It was estimated that about two hundred thousand people had come out to welcome Joe Knowles home (picture to left).

The adventure story created by Joe Knowles had given a tremendous circulation boost to the Boston Post and this fact did not escape the competing newspaper, the Boston American, owned by William Randolph Hearst. Although the Boston American had published several columns trying to discredit Knowles as a fraud, the following year, 1914, the San Francisco Examiner, another Hearst newspaper, sponsored a west-coast version of what Knowles had done in Maine. It was decided that this adventure would take place in the Siskiyou Mountains, a decision would bring this bizarre publicity stunt, and the story that would be told nationally, to the front door of Josephine County.

1914 – Siskiyou Mountains

A photograph of Knowles before he disappears into the wilderness after a short visit with associates on August 8, 1914 (23). East Fork of Indian Creek, Siskiyou Mountains.

There was no doubt that the idea of a man going into the woods completely naked to live off the land for two months would be an eye catcher in any headline. However, the Examiner had learned an important lesson from the Knowles’ experience in Maine, or more specifically, from their sister newspaper, the Boston American, who published several aggressive articles declaring Knowles’ adventures to be a farce. The attacks were more likely intended to undermine the integrity of the competing newspaper than to defame Knowles but there was a valid concern that without having a way to verify Knowles’ claims, the Examiner would be vulnerable to the same types of attacks. For this reason, they hired two professors and a photographer to go along and set up an observation camp on the fringe of the wilderness where Knowles would conduct his experiment (9).

The Examiner wasted no time sensationalizing the story and the fact that there were cougars in this region inspired the banner announcement: WILD BEASTS ROAR INVITATION TO JOE KNOWLES. With this introduction echoing through the media, Knowles arrived in Grants Pass on 13 July, 1914 where he added his own dramatic flare to the mix of publicity. In an article printed in the July 22, 1914 edition of the Grants Pass Daily Courier Knowles stated, “if I do not meet a bear, a cougar or other wild animals I would regret it very much and should any of these animals show themselves, they will not get away.”

The following day, Knowles and others in his group left by auto for the forested slopes of the Siskiyou Mountains by way of a road that followed Sucker Creek to Camp Three Creeks, a campground that had been established by the Caves Camp Company at Josephine County Caves (Oregon Caves). This was likely the end of the road and the place where the Caves Creek Trail to Oregon caves began. They thought the experiment might start at this camp or at the caves themselves (29).

Doctor Edwards was one of the persons given responsibility for assuring Knowles conducted his experiment without assistance. He is seen sitting outside the “observation outpost” an abandoned miners cabin near Indian Creek, Siskiyou Mountains (18).

The group scouted around for a suitable place for Knowles to conduct his man against nature experiment and returned to Grants Pass to announce that conditions found along the East Forks of Indian Creek near the Oregon-California line were ideal for the wildest undertaking a man would wish to experience (7).

The Daily Courier described Knowles’ upcoming adventure saying “Knowles will take up the battle with nature, providing himself with food and clothing from the mountains and streams. Traps and snares he must make with his unaided hands. Fire he must kindle by methods he says are easy without matches, without flint and steel. Fish he will get without hook and game without steel traps (2).”

Knowles and his group returned to Illinois Valley by automobile where they met a guide at the town of Holland and rode from there by horseback to an observation camp at a mining cabin in the Indian Creek drainage (9). There was very likely a well traveled pack trail to the Bolan Lake area where the owner of the Holland Store had set up a supply station near Bolan Lake for miners during the gold rush that followed the 1904 Briggs gold strike about four miles east of Bolan Lake (28). There was also a Forest Service lookout station on Bolan Peak (10). After Bolan Lake, the trail became more difficult to follow because of thick brush (10).

The location of the cabin was not far from Bolan Mountain because Knowles noted that he could see Bolan Mountain to the north of the observation camp site (9).

On July 21, Knowles gave all his clothing to his associates and disappeared into the forest. There was but little ceremony about the departure. It had been planned by the people of Grants Pass to be present and a party of more than 60 had planned to see him off, but the location that had been chosen by Professor Waterman to assure Knowles did not have human contact during the experiment, was remote and difficult to access and made it impossible for the party to get to the point where Knowles made his departure (9).

The nights were cold but Knowles claimed “he would sleep as comfortably in his bed of moss and leaves with his friction-made fire as he does at the hotel with artificial clothing”.

Knowles said his first attention would be given to covering his feet using bark woven basket-like over his feet using bark of the “white cedar” for a sole (probably Port Orford cedar). This footwear would suffice until he could secure skins for moccasins. Then his hunting for large wild animal will begin. However, Knowles feet became swollen and infected within the first days of his adventure, which he thought had been caused by poison (19). He later claimed he could hardly walk and reportedly was able to heal the injuries with herbs made from surrounding plants and a balsam made from fir trees (19)

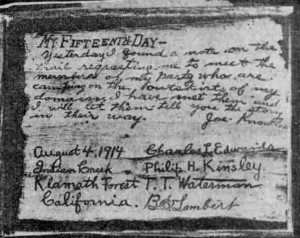

Knowles meets others for a short visit at his Indian Creek camp after two weeks of being in the wilderness alone. Left to right – Dr. Waterman, Joe Knowles, Philip Kinsley (newspaperman), and Professor Edwards (23).

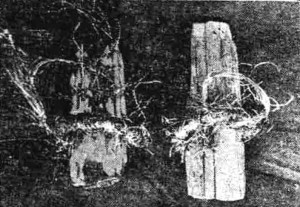

Knowles wrote progress letters in much the same way he had in Maine; written on bark using charcoal from camp fires (18). One of these reports was mentioned Knowles had found a deer that had been killed by a mountain lion and he had used the hide of the dead deer to make clothing (4, 17). He noted that the temperatures had been too cold in the high elevations and he was seeking lower, warmer levels (4). He reported that his sustenance has been mainly on fish which are easy to capture along with small game and an assortment of berries, nuts and roots (19).

The man versus nature story was going along just as expected but one month into the experiment, the outbreak of World War I eclipsed the drama of the Knowles adventure. This may have been one of the reasons why Knowles decided to return to civilization after 30 days in the wilderness but a more likely reason was the difficult conditions he encountered in the Siskiyou Mountains.

A special train was sent out on the California & Oregon Coast Railroad to meet the automobile carrying Knowles back from the wilderness. They met at the Applegate River where the bridge was still under construction. The train carried Knowles to the crossing on Sixth Street where he was greeted by the Moose Lodge band and many automobiles which escorted him to the Oxford hotel. He later put on the clothing he had made in the wilderness and walked around the streets of Grants Pass to talk with the curious residents.

The next day he departed by train for Portland and eventually back to San Francisco.

The rest of the Knowles story

Joe Knowles in deer skin clothing he was wearing when he emerged from the wilderness of the Siskiyou Mountains on August 21, 1914 (see 25). Photo from Josephine County Historical Society.

After Josephine County, Joe Knowles would attempt one more wilderness adventure. This time Hearst sent Knowles to team up with the New York Journal where he was to spend two months surviving in the Adirondacks. In the Hurst tradition of sensational journalism, the adventure would include a female counterpart, the Dawn Woman, who was to strip to complete nudity and conduct a female’s version of man against nature. Her name was Elaine Hammerstein, a noted theater and silent film star of her day and the daughter of Broadway producer Arthur Hammerstein (uncle of legendary composer Oscar Hammerstein II). She had been selected from among three-dozen contenders for the Dawn Woman title.

Knowles spent time training her in basic survival skills and they were to enter the woods at the same time but in different locations where they were not to make contact with each other. However, the mosquitoes were apparently too much for her and after seven days by herself in the wilds she quit and went home. Knowles saw no reason to continue with the experiment and also exited the woods.

Knowles eventually moved to Ilwaco, Washington, the end point of the Lewis and Clark expedition and about as far from Maine as he could get. He died there on Oct. 22, 1942

References

1) Carson, Gerald, 1981. Naked Tarzan, Yankee Heritage Magazine. http://www.americanheritage.com/articles/magazine/ah/1981/3/1981_3_60.shtml

2) Grants Pass Daily Courier, July 15, 1914, pg 1: Joseph Knowles and his wilderness stunt

3) Grants Pass Daily Courier, July 22, 1914, pg 1: Grants Pass gave Knowles God speed

4) Grants Pass Daily Courier, August 5, 1914, pg 1: Cougar kills deer for Joe Knowles – The skin will make covering, sinews thread, bones tools

5) Grants Pass Daily Courier, August 26, 1914, pg 1: Joseph Knowles is the first passenger – Nature Man greeted by big crowd at Grants Pass

6) Montavalli, Jim. Naked in the Woods

7) Oregonian, July 17, 1914. Naked man enters forest Monday, p15

8) Oregonian, July 21, 1914. Naked man enters wilderness today, p1

9) Oregonian, July 22, 1914. Knowles is off on wilderness war; camp almost inaccessible, p1

10) Oregonian, July 23, 1914. Scientist watch Knowles ply wits, p1.

11) Oregonian, July 26, 1914. Knowles sighted; bark wraps legs: Campers run across Nature Man 10 miles from start, p8.

12) Oregonian, July 27, 1914. First word comes from man in wilds, p3.

13) Oregonian, July 28, 1914. Knowles’ message relief to friends, p5.

14) Oregonian, July 29, 1914. Knowles’ task is struggle to exist, p5.

15) Oregonian, July 31, 1914. Knowles keeps on with feet injured

16) Oregonian, August 1, 1914. Knowles’ success seen, p11.

17) Oregonian, August 4, 1914. Deer, lion killed, found by Knowles, p5.

18) Oregonian, August, 5, 1914. Charcoal his pen, p7. (photos)

19) Oregonian, August 7, 1914. Fir balsam heals Knowles’ bruises, p13.

20) Oregonian, August 9, 1914. Nature Man met, p4.

21) Oregonian, August 13, 1914. Knowles gets deer, p12.

22) Oregonian, August 14, 1914. Knowles’ time ending, p7.

23) Oregonian, August 16, 1914. Joe Knowles near end of test living in woods as primitive man, p10. (photos).

24) Oregonian, August 21, 1914. Knowles emerges from lone woods, p14.

25) Oregonian, August 22, 1914. Knowles back in civilization again, p4. (photos)

26) Oregonian, August 23, 1914. Knowles’ camp is visited by party, p7.

27) Oregonian, September 5, 1914. Joe Knowles seen in primitive garb, p16. (photos)

28) Pfefferle, Ruth, 1977. Golden Days and Pioneer Ways. Josephine County Historical Society, Grants Pass, Oregon, p13.

29) Medford Tribune, July 14, 1914. Nature Man to live in Grants Pass wilds 60 days, p6.

Other sources

Oregonian, July 16, 1914. Naked man faces test, p19.

Oregonian, July 17, 1914. Mr. Knowles’ simple life, p10.

Oregonian, July 19, 1914. Nature Man starts on trip Tuesday, p7.

Oregonian, July 24, 1914. Knowles craft is primitive fine art, p1.

Oregonian, August 2, 1914. Knowles’ fourth message due soon

Oregonian, August 3, 1914. Pastor of Methodist Church gives praise to Knowles, p7.

Oregonian, August 9, 1914. Knowles’ home found, p6.

Oregonian, August 11, 1914. Test held honest, p5.

Oregonian, August 19, 1914. Knowles is due to quit woods today, p6.

Oregonian, August 27, 1914. No real value in experiment, p6.

Oregonian, August 28, 1914. Coping power is all, says Knowles, p7.

Oregonian, August 30, 1914. Object lesson furnished by Joe Knowles’ stunt is valuable one, p8.

Haefner, Henry, 1974. The Octogenarians. Notes from the Knight Library Special Collections, University of Oregon. Page 61